INDONESIAN AND NYC

Indonesians in New York City mostly live in and around Elmhurst, Queens a traditionally Asian/South East Asian neighborhood. The population of Indonesians is relatively small compared to the other nationalities living in Queens, and the community is therefore tight knit.

Though over 300 different languages are spoken in Indonesia, Bahasa Indonesia is the lingua franca both in Indonesia and in New York City. As a result, though many Indonesians are multilingual, in New York, they essentially become bilingual, relying primarily on English and Bahasa Indonesia. In this project, we explore how permanent versus temporary spaces affects language use, drawing parallels to the ways in which smaller Indonesian languages may be sporadically used, but Bahasa Indonesia is the permanent language of the diasporic community.

OVERVIEW

As one of the largest archipelagos in the world, with more than 17,000 islands, the geography of Indonesia is made up of enclaves within enclaves. 300 ethnic groups with different values, appearances, and religions are bounded by an effort of nationalism and the longing for independence. Today, the foundations of Indonesian identity have been situated in religion and language, a dynamic that both brings the country together and divides it.

“Divinity for unity” is the official motto and offers a foundational philosophy of the country. This reflects the importance of religion in Indonesia. The identification card contains each citizen’s religious information, and religious institutions are a central point of neighborhoods and cities.

The Youth Pledge, written in 1928 states “we the sons and daughters of Indonesia, respect the language of unity, Bahasa Indonesia”, in turn, promising unification in both language and nation. Bahasa Indonesia might be the official language of the country, but it is only the mother tongue of 7% of the population.

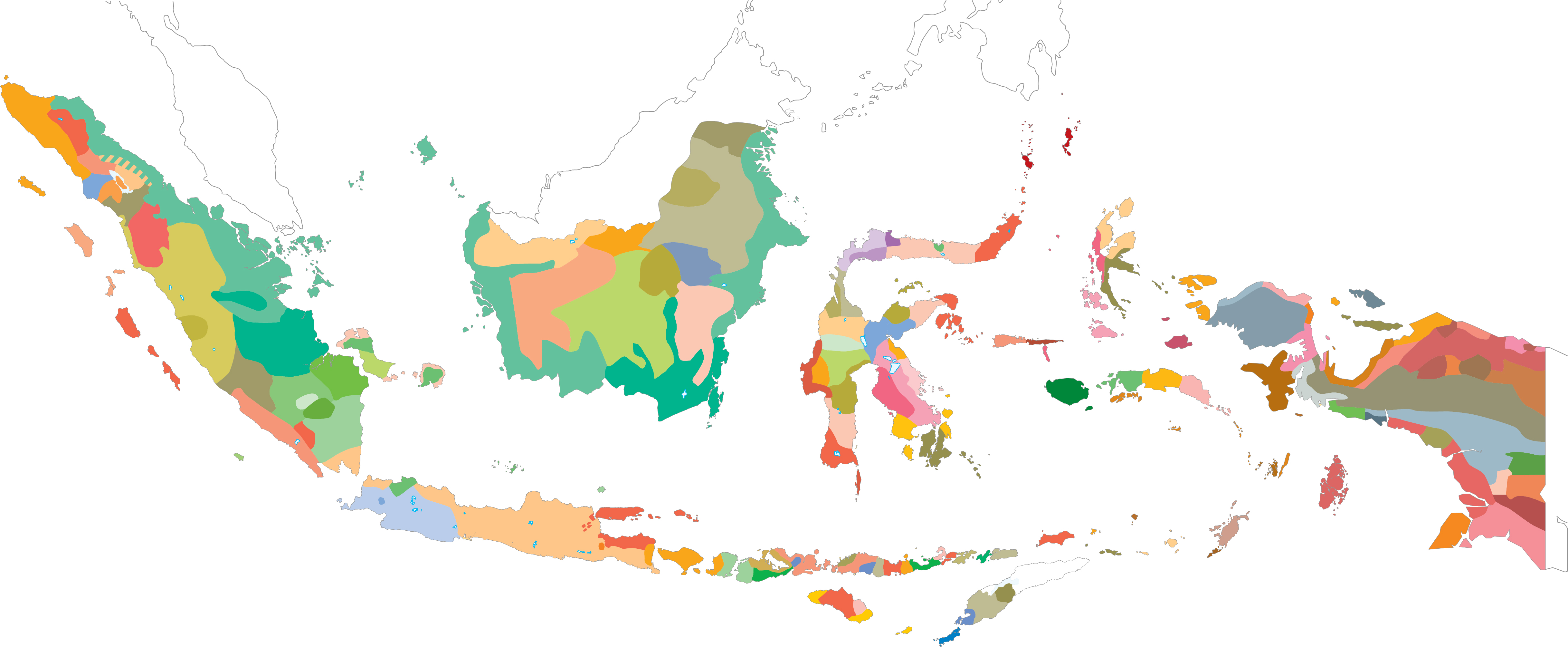

Some of the 726 regional languages are growing while some others are dying. Kymlicka defines a societal culture as one “which provides its members with meaningful ways of life across the full range of human activities, including social, education, religious, and economic life, encompassing both public and private spheres (footnote). These cultures tend to be territorially concentrated, and based on a shared language.” In this way, Bahasa Indonesia has assumed an important role in establishing the societal culture of Indonesia in the face of the geographical features that have shaped different cultures and beliefs . Today, Bahasa Indonesia is growing stronger: more than 80% of Indonesian citizens speak it as a second language.

Even amidst these unifying efforts, conflict in Indonesia is common. During 2001, there was an outbreak of inter-ethnic violence in the town of Sampit, Central Kalimantan, between the indigenous Dayak people and the migrant Madurese. In 2002, the Government signed peace deal in Geneva with the separatist Free Aceh Movement (GAM), ending 26 years of dispute. Earlier this year, a protest was held during DKI Jakarta Governor Election, using race and religion issue as political drive.

According to the American Community Survey of 2010, there are around 5000 Indonesians in New York City. Most of these people came during 1990s to escape political situation in Indonesia. Today, the number of Indonesians in New York City continues to grow, and as the community grows, it is also becoming more diverse. The changing demographics of the Indonesian diaspora prompts the question: are the ethnic, religious, and linguistic tensions within Indonesian society replicated in New York City?

LINGUA FRANCA AND IDENTITY

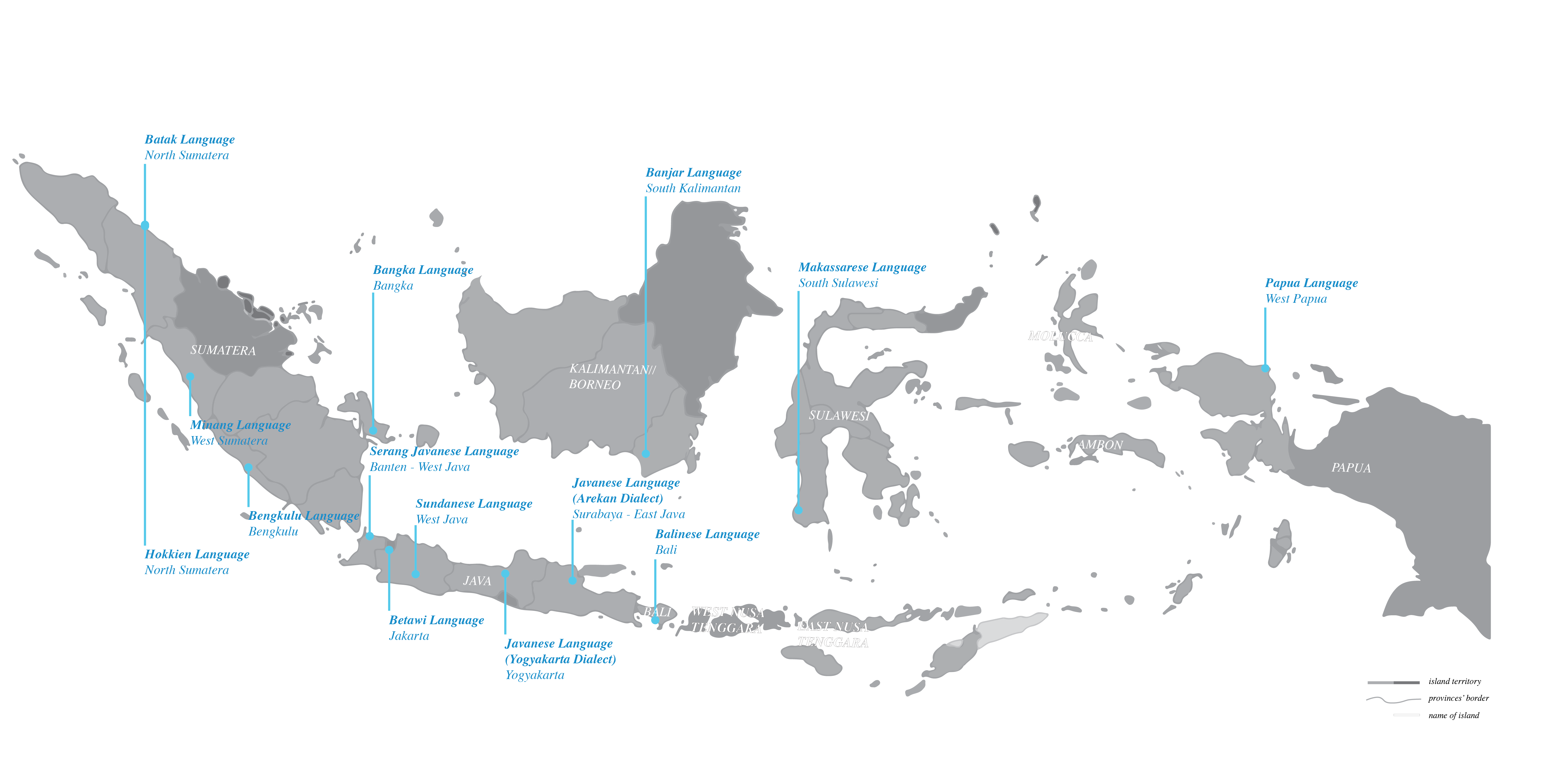

In the post-colonial era, the diversity of Indonesian cities is increasing, but language and ethnicity remain deeply connected. We asked respondents from different areas to say different things to illustrate the level of linguistic diversity in Indonesia: Click To Enlarge

1) Say 1-2-3 in their regional language:

Balinese Language, Bali

Serang Javanese Language, Banten - West Java

Betawi Language, Jakarta

Javanese (Arekan), Surabaya - East Java

Sundanese Language, West Java

Javanese Language (Yogyakarta), Yogyakarta

Banjar Language, South Kalimantan

Papua Language, West Papua

Makassarese Language, South Sulawesi

Bangka Language, Bangka

Batak Language, North Sumatera

Hokkien Language, North Sumatera

Minang Language, West Sumatera

2) Say ‘sudah makan belum?’ - meaning “have you eaten?” in their regional language:

Balinese by Paul

Serang Javanese by Satria Javanese (Arekan) by Arina Java Betawi by Miftah Sundanese by Kania Sundanese Pikaseurieun by Kania Sundanese by Rahmi Javanese (Yogyakarta) Kromo Level by Janu Javanese (Yogyakarta) Ngoko Level by Anggoro Banjar by Nova Banjar by Rina Makassarese by Karim Bangka by Shofi Bengkulu Language by Toni Batak by Robinson Batak by Sri Hokkien by Rhea Minang by Doni Minang by Ryan

3) Say ‘sudah makan belum?’ - meaning ‘have you eaten?’ in Bahasa Indonesia in their regional accent:

Bahasa Indonesia Balinese by Paul Bahasa Indonesia Serang Javanese by Satria Bahasa Indonesia Betawi by Miftah Bahasa Indonesia Sundanese by Kania Bahasa Indonesia Sundanese by Rahmi Bahasa Indonesia Javanese (Yogyakarta) by Janu Bahasa Indonesia Javanese (Yogyakarta) by Anggoro Bahasa Indonesia Banjar by Nova Bahasa Indonesia Banjar by Rina Bahasa Indonesia Makassarese by Karim Bahasa Indonesia Bangka by Shofi Bahasa Indonesia Bengkulu by Toni Bahasa Indonesia North Batak by Sri Bahasa Indonesia Hokkien by Rhea Bahasa Indonesia Minang by Ryan Bahasa Indonesia Minang by DoniLANGUAGE AND IDENTITY | SPACE IN BETWEEN

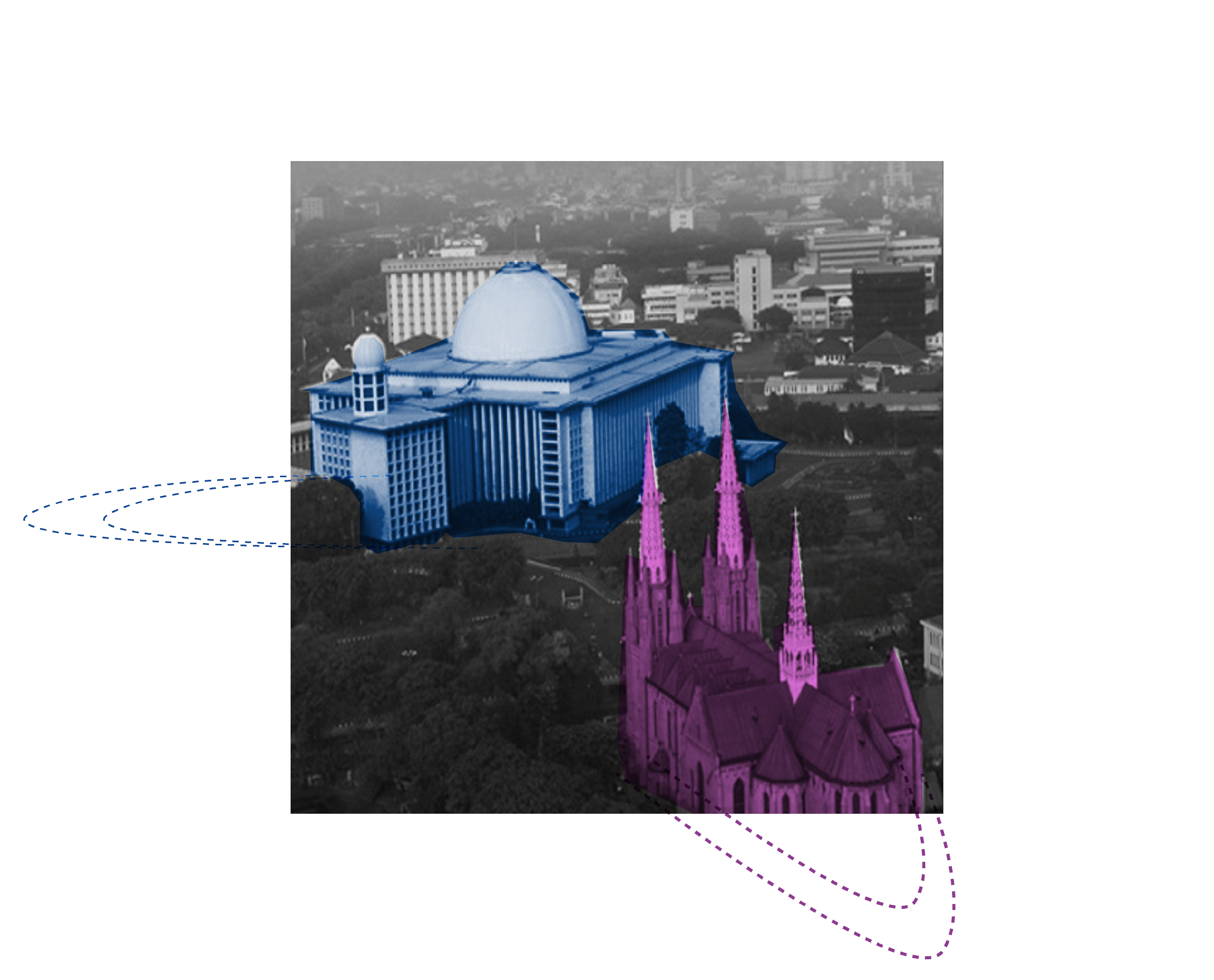

Whether it is a Vihara for Buddhists or Church for Catholics, religious spaces in Indonesia are never used only for religious purposes. The spaces are always used for a variety of community functions. As most of the religions in Indonesia originated outside the country, the language of the religious spaces’ architecture depicts an mixing of cultures. Buddhist Viharas and Hindus Puras feature Sanskrit inscriptions and South Asian architecture, meanwhile Christian churches feature Latin inscriptions and European architecture, while Confucian temples are inscribed with Mandarin and Muslim Mosques are, with Arabic.

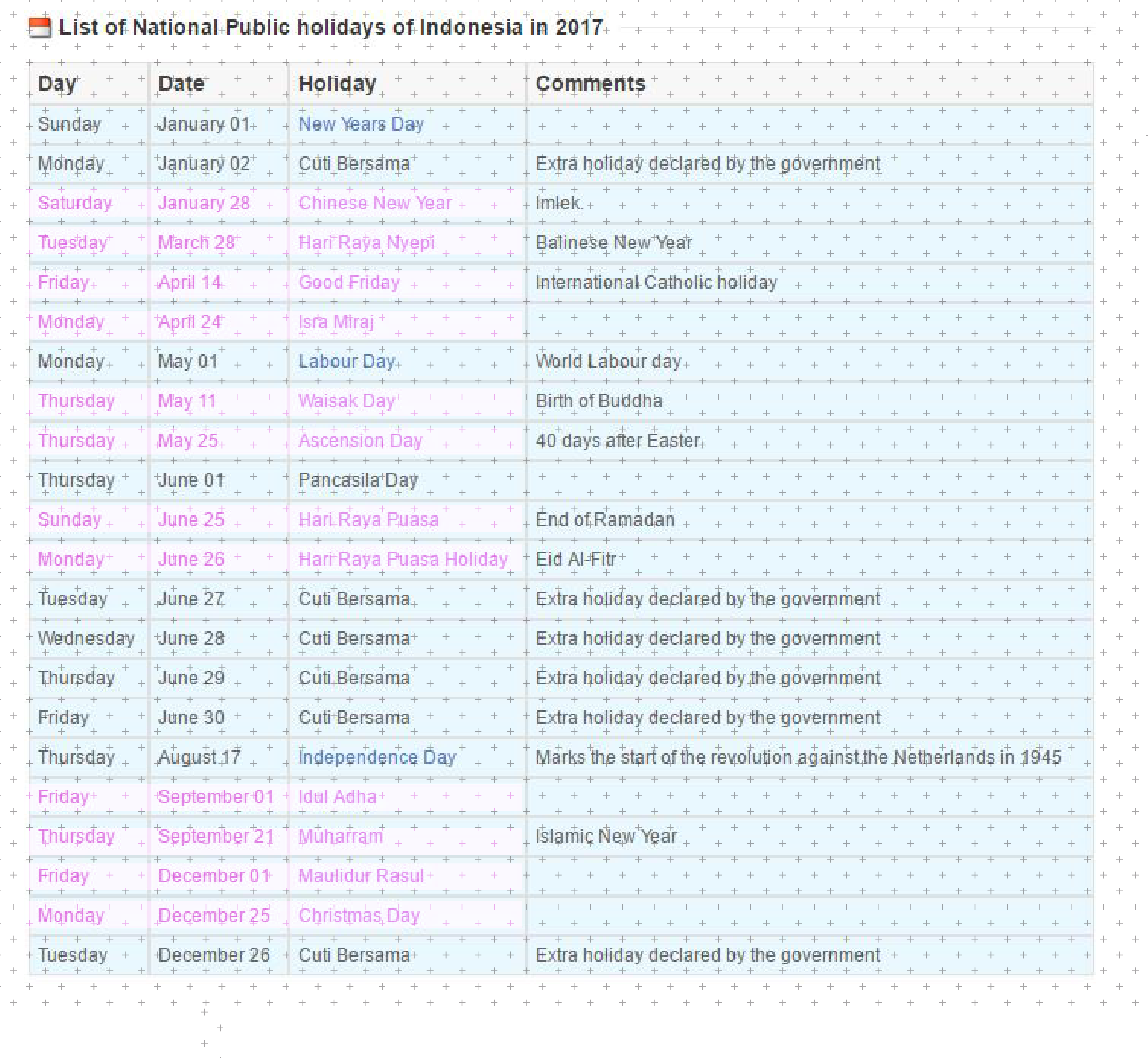

Religious spaces are not free spaces, even though most are open to public. There are boundaries between spaces, and hierarchies within them. In an attempt to encourage respect and tolerance, the Indonesian government has made all of the celebrations of the six recognized religions national holidays.

Outside the identity of a devotee, Indonesians interact through other spaces such as food bazaars and Independence Day activities.

Indonesians in New York City: A Sense of Unity

Click Map Thumbnails to Enlarge

Indonesians in New York call Elmhurst ‘kampung Indonesia’ or Indonesian village. The feeling of being in New York slightly diminishes as people talk in Bahasa Indonesia or their own dialect, purchase Indonesian foods and groceries, and pray together.

“Even where citizenship has been granted, immigrants are expected to integrate as quickly as possible, and this usually includes the obligation to learn a new language, often under trying circumstances that make few allowances for the learning difficulties they may actually face.” - (Wee, 2010)

In Elmhurst, most Indonesians are able to speak English but many, especially the first generation, are not fluent. Most second and third generation Indonesian-Americans speak American English and some speak Mandarin as well, an effect of contact with Mandarin speakers in New York City.

Simone (2004) highlights just how interdependent diasporic communities can feel to the members, noting that “while immigrant networks depend on the constant activation of a sense of mutual cooperation and interdependency, these ties are often more apparent than real—especially as a complex mixture of dependence and autonomy is at work in relations among compatriots.” To members of the New York City Indonesian community, this can feel amplified – as being Indonesian binds members together even when they would have identified as being separate in Indonesia.

To highlight how this is reflected in the city, we explored how Indonesians inhabit urban spaces. There are essentially two types of spaces: permanent and temporary. Permanent spaces are spaces closely associated with the Indonesian community. If a newcomer were to ask where to find other Indonesians, they may be sent to the Consulate General of the Republic of Indonesia, a mosque, a church or a particular grocery store. By contrast, temporary spaces are often cultural events hosted and attended by members of the Indonesian community. If a non-Indonesian New Yorker were to ask where to learn about Indonesian culture, they might be directed to some Indonesian restaurants around Elmhurst, NYU, or other mosques and churches where pop-up bazaars occasionally happen. Different spaces display different patterns.

The permanent spaces replicate the boundaries found in Indonesia: The Consulate General building is an official and formal space where everyone uses Bahasa Indonesia, just as they would in a government building in Indonesia. Yet at Al Hikmah mosque, members come together in Arabic, aligning with the lingua france of the Muslim community rather than the Indonesian one. Meanwhile, Bethany Church in Queens is a co-owned space of Christian communities where they use Bahasa Indonesia as the official language but hosts an English interpreter too. There, the community is more homogeneous (East Javanese), and the Javanese language is incorporated in the services.

Temporary spaces do not reflect the same boundaries of tribes, ethnicities, languages or religions and sometimes act as an introduction of Indonesia to foreigners rather than to other Indonesians. The use of Bahasa Indonesia is dominant within these spaces, dissolving personal linguistic identities into a bigger collective identity.

Across spaces, the tensions which have shaped Indonesia today are not reflected in the Indonesian community in New York City. There are enclaves and boundaries that set apart some sub-groups of this community yet there are more spaces where members collaborate and mingle. The struggle to survive in New York City has glued the Indonesian community together and strengthened their collective identity first as Indonesian. Bahasa Indonesia plays an important role in binding the community together regardless of other linguistic differences.

Dissa Pidanti Raras

MSAUD, 2017, Urban Design

Shuman Wu

MSAUD, 2017, Urban Design

Indonesian & NYC

Indonesian & NYC