Raza v. New York

In June 2013, the ACLU, the NYCLU, and the CLEAR project at CUNY Law school filed a lawsuit against the NYPD for religious profiling and surveillance, on behalf of three religious and community leaders: Imam Hamid Hassan Raza, Mohammad Elshinawy, and Asad Dandia. The other plaintiffs included were two mosques: Masjid At-Taqwa and Masjid Al-Ansar, and the charity Muslims Giving back.

The legal document of the Raza v. New York City court case was released to the public in June 2013. This document contains details about the different incidents of surveillance experienced by each plaintiff and the effect that this had on their lives and communities. These incidents have helped us to track various cartographies of the NYPD’s surveillance of Muslim communities in Brooklyn and the subsequent proliferation of new modes of existence. We have tried to elucidate these three cartographies in the map above, looking at the stretch of spaces and years in which the NYPD infiltrated and extensively surveilled Muslim charities, mosques, and homes.

The case was settled in 2016. One of its remarkable victories was that the settlement included a number of protections that prohibit the NYPD from investigations in which race, religion, or ethnicity is a substantial or motivating factor.Code-Switching

Code-switching is the practice of using one dialect, register, accent, or language over another, depending on the social or cultural context to project a specific identity. It can also mean the modifying of one's behavior, appearance, etc., to adapt to different sociocultural norms. The phenomenon of self-censorship was common among Dandia, Elshinawy, and Raza. Self-censorship is a kind of code-switching. In these cases, code-switching refers to the practices of employing or avoiding a certain vocabulary in certain spaces. This vocabulary is not in itself incriminating, but in the post-9/11 era, when Muslims are all treated as potential terrorists by law enforcement, criticism of U.S. foreign policy for example, can be used as evidence against an individual.Mapping Raza v. New York

This research into the the case has culminated into maps and illustrations that are meant to complement and enhance the legal evidence presented in court. These mappings build on discourse opened up by Eyal Weizman and others in Forensic Architecture. Like Forensic Architecture, our aim is to “bring new material and aesthetic sensibilities to bear upon the legal and political implications of state violence”Our maps and illustrations attempt to elucidate this information and present it in relation to "code-switching," showing the settings in which the plaintiffs had to adjust their language.

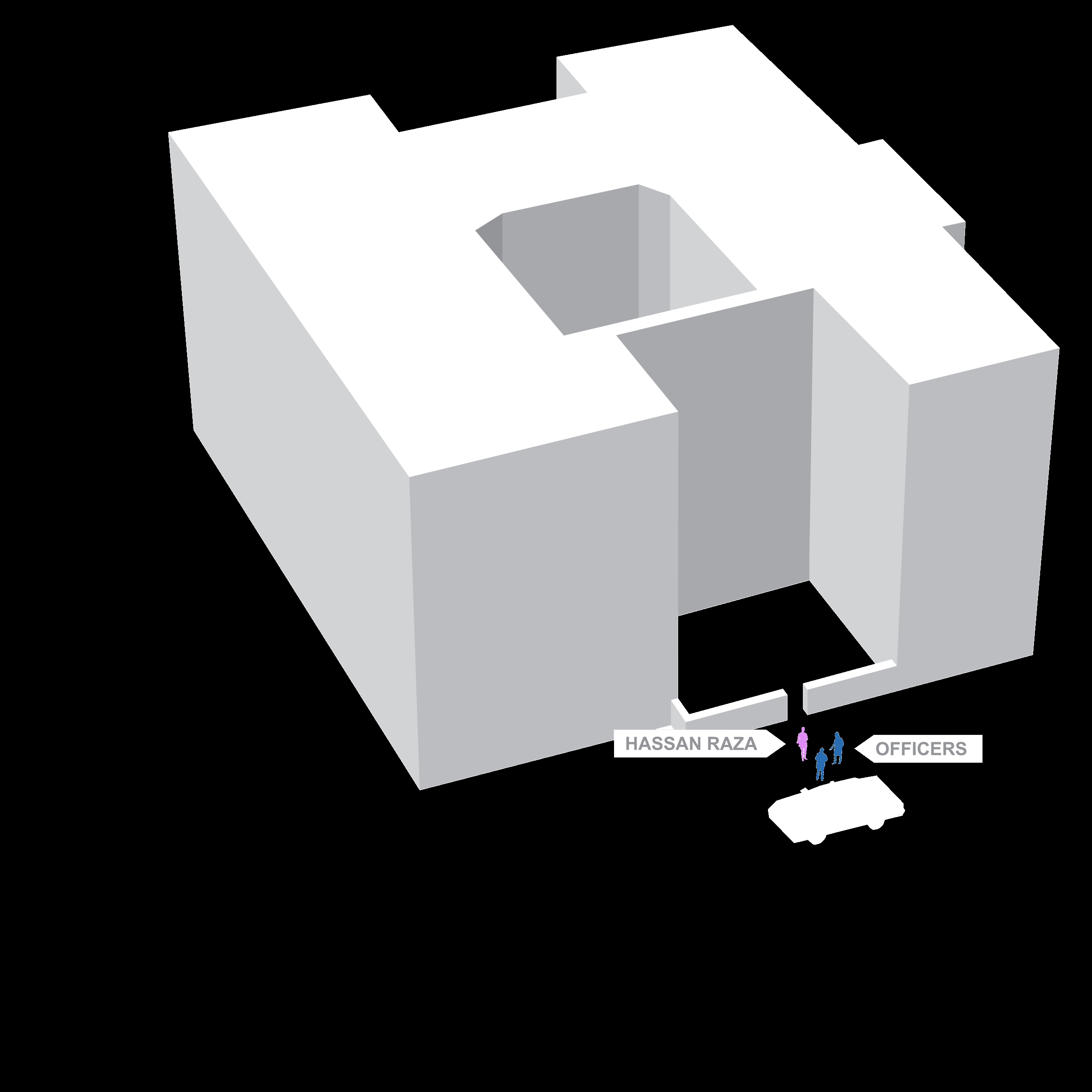

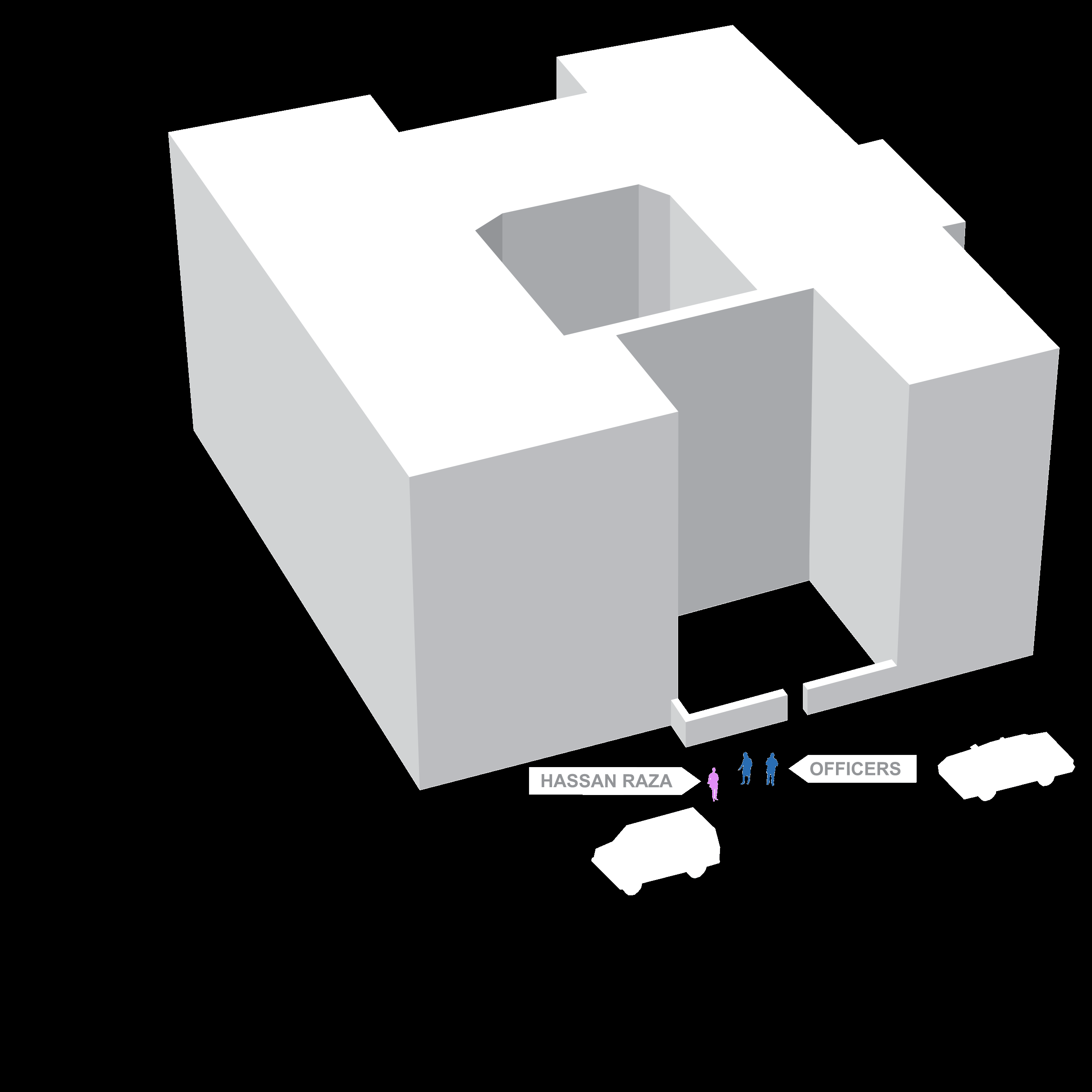

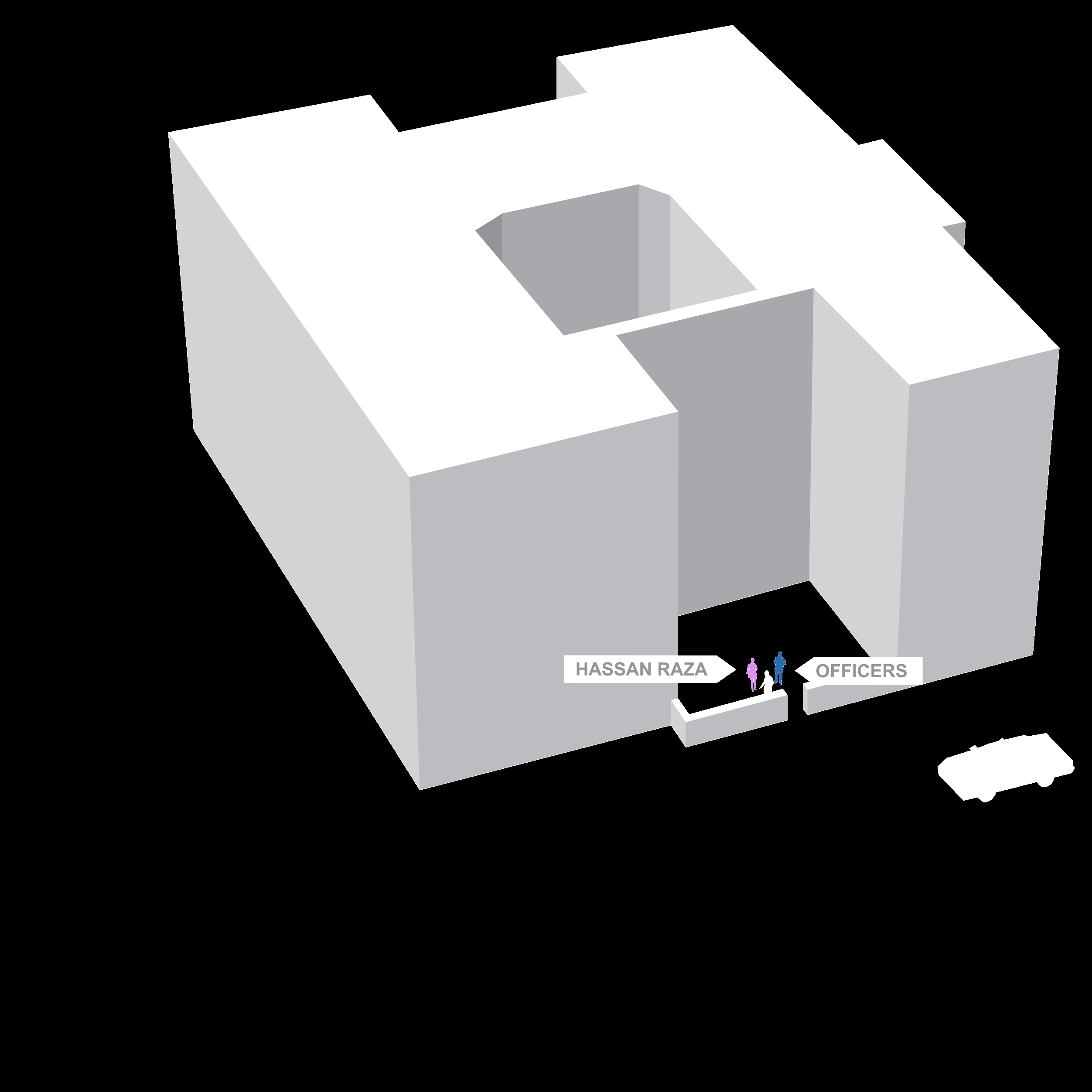

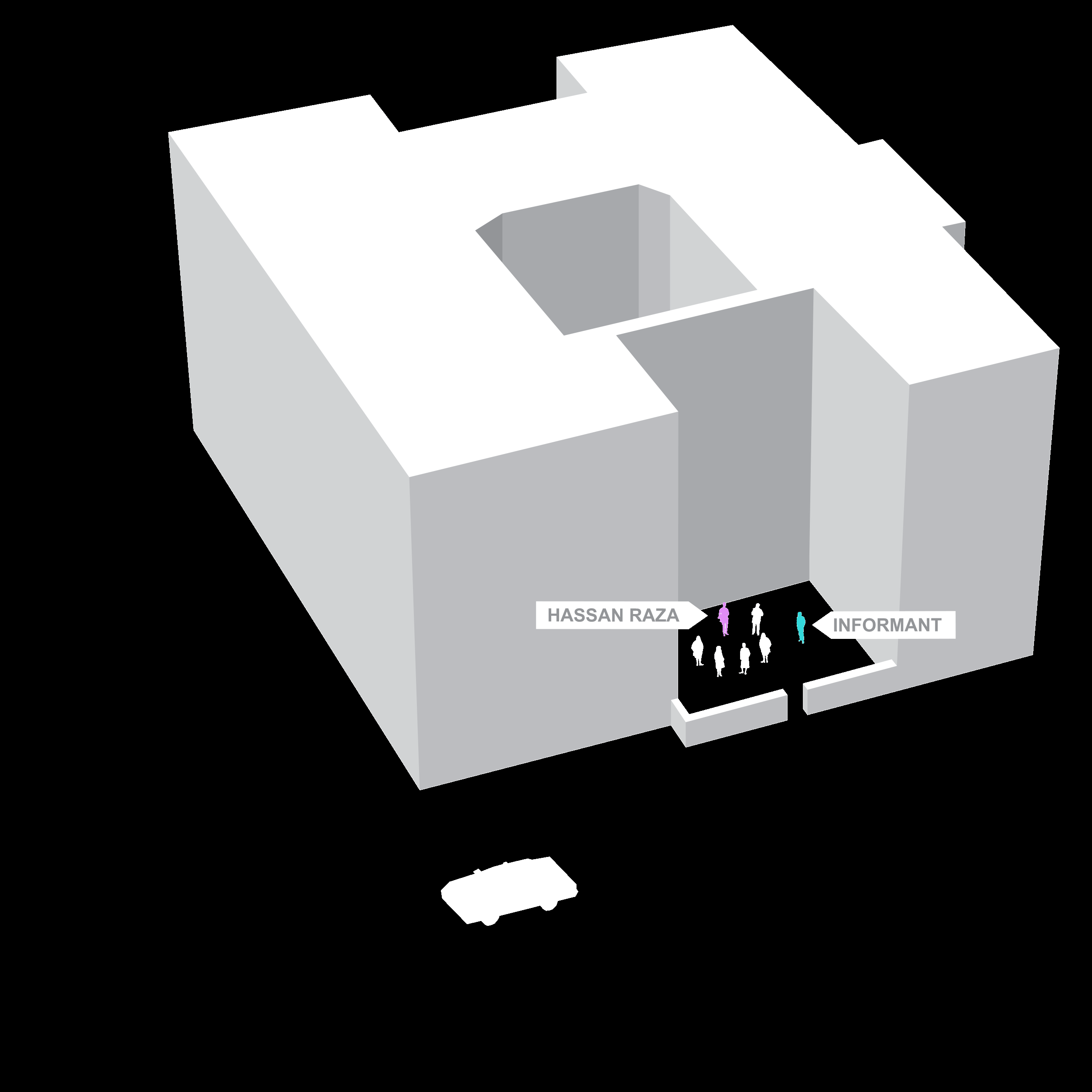

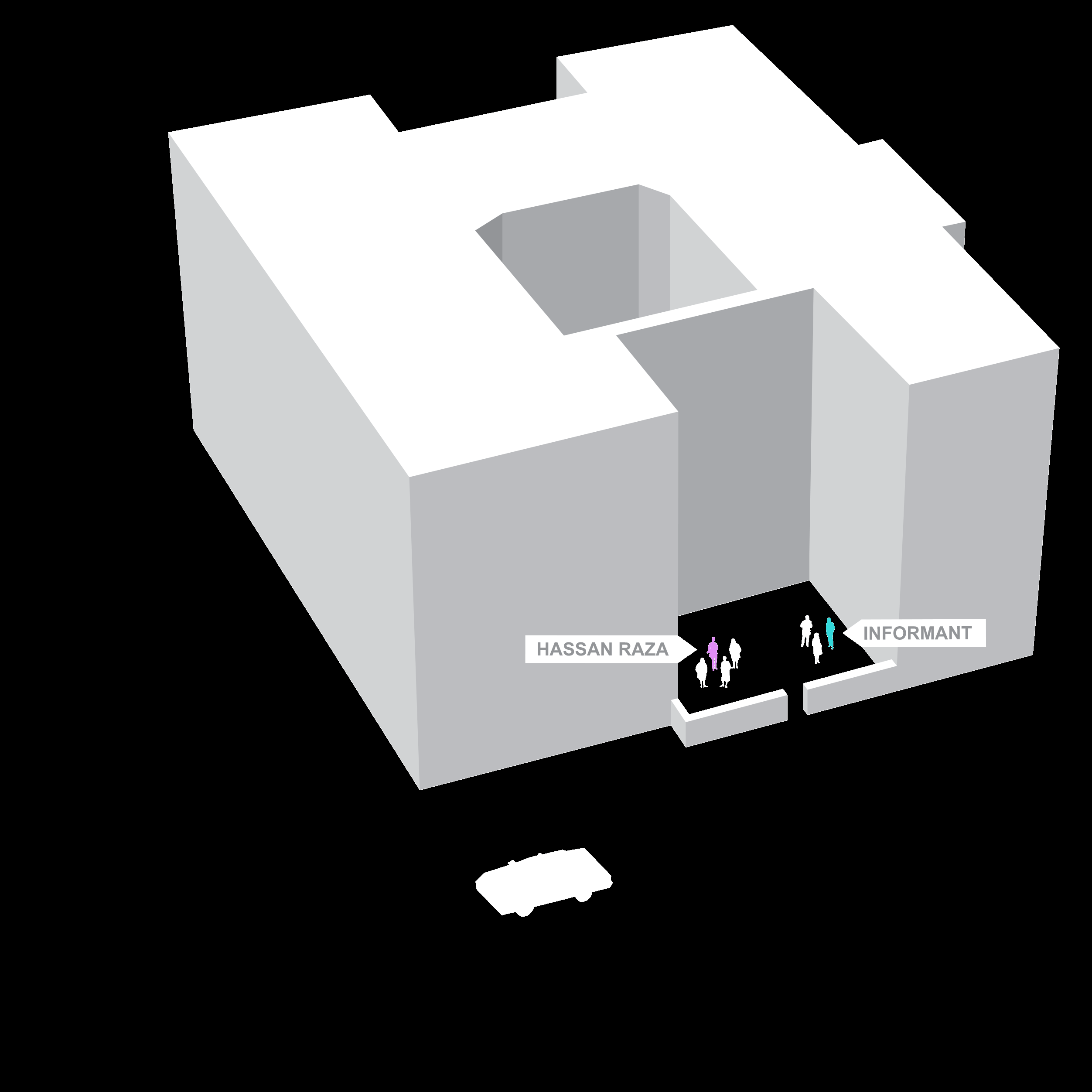

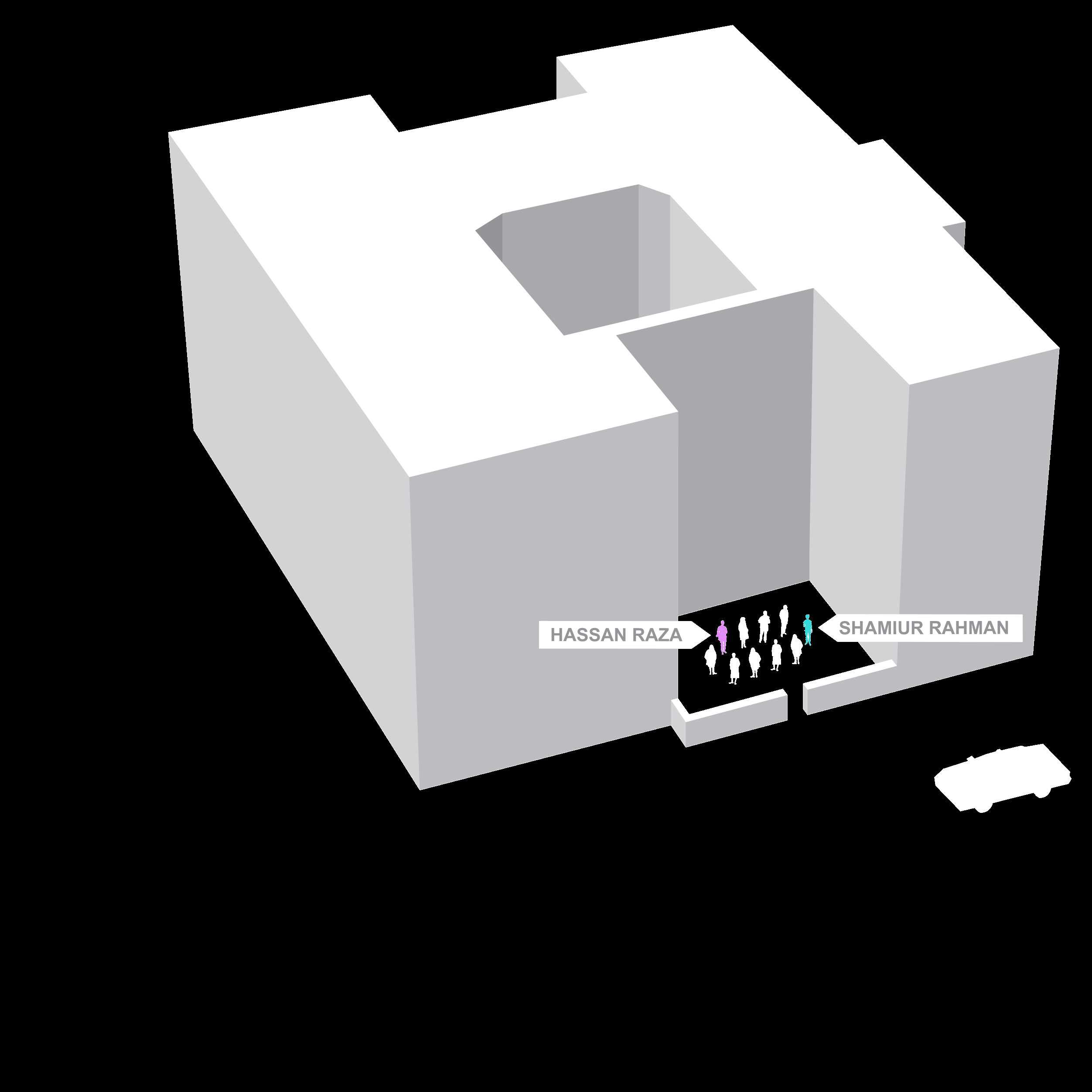

The series of illustrations below depict various incidents of surveillance that occurred to Imam Raza between 2009 and 2012, at Masjid Al-Ansar Mosque in Brooklyn.

The interactive narrative map below is another depiction of the incidents highlighted as moments of unconsistutional surveillance in the court case Raza v. City of New York, this time depicting the surveillance of Mohammad Elshinawy and Asad Dandia, as well as Imam Raza.

View Map in Full Screen

NYPD Surveillance in Brooklyn

The NYPD conduct their surveillance not only by tailing individuals, but also by collecting data on entire communities. The data depicted below was collected from a document produced by the NYPD Special Demographics Unit that mapped "Locations of Interest" relating to individuals with Egyptian ancestry on July 7th, 2006. The document was later leaked by the Associated Press in the lead up to the court case.

The map is a heat map. This blurs the specific locations that were targeted, but gives an indication to where NYPD surveillance activity took place in Brooklyn.Self-Surveillance as Protection

The court case was prefaced by a series of articles and leaked files published in 2011 by the Associated Press on NYPD surveillance of Muslims. After the documents were leaked, lawyers form the ACLU report that “the environment of suspicion and fear only became more acute, both for Imam Raza and for Masjid Al-Ansar’s congregants”

Slow Violence

The NYPD deployed uniformed and plainclothes police officers, informants, and in their silent omni-presence slowly eroded trust in the plaintiffs’ respective communities. There was no sensational moment of police transgression, no raids or smashed doors. Rather, there were accumulated threats and suspicions, accusations and looming fears. This kind of violence, subtle and perhaps even “intangible” in the traditional use of that word, is analogous to Rob Nixon’s use of “slow violence” to refer to the slow degradation of ecosystems and their dependent communities."Tangible Evidence"

Prior to the Raza v. City of New York case, there were no precedent for suing successfully on the grounds of surveillance. Judges dismissed charges against the police in the Hassan v. City of New York trial of 2012, for example, on the grounds that there was no “evidence of tangible harm.”Self-Censorship

The NYPD's unconstitutional and Islamophobic surveillance practices are backed up by literature they produce such as the 2007 report: “Radicalization in the West: the Homegrown Threat.” This contains assertions such as:

“As these young Muslims explore their Islamic identity, their activist spirit causes them to gravitate to the more militant message of jihadi-Salafi Islam—a message that calls for aggressive action rather than steadfastness and patience.”In addition, the NYPD actually instructed its undercover cops to actively provoke people into saying things they deemed incriminating. Shamiur Rahman, the former NYPD informant who was involved in spying on Raza, Dandia, and Elshinawy, admitted in an op-ed that he would try to “bait” people into saying potentially incriminating things. He was instructed by the police to use a strategy that they called “create and capture,” whereby he would start a provocative conversation in order to then record the responses of the people around him.6

Practices of self-censorship and code-switching were used by all plaintiffs as measures to protect themselves. The complaint detailed the following about Imam Raza:

“Raza does not discuss in his sermons or with his congregants certain topics that might be perceived by the NYPD or its informants as controversial or that might be taken out of context. These topics include current events like the war in Afghanistan. They also include the concept of jihad, which Im am Raza refrains from discussing despite his belief that jihad, which means “struggle,” concerns the internal and universal struggle for human self-improvement, that it is a struggle in which all human beings are engaged, and that it is the most important struggle in Islam.”8

In a 2016 op-ed Elshinawy wrote:

“After 2013, I began creating mental filters through which to run my speech in sermons and among my peers holding back anything that could be seen as controversial. In my lectures, I played down Islamic values of valor and heroism, worrying that informants would assume, incorrectly, that I was promoting aggression or violence. I hesitated before publicly discussing the devastation faced by innocent civilians in the Muslim world, in case someone distorted my lessons on empathy as something “anti-American.”9

Dandia too, echoed these sentiments. In an interview, he said the following:

“The idea that there is potentially a mechanism watching you forces you to surveil yourself. You have to be conscious of what words you use, what terminology you use, the ideas you allow yourself to engage with. You know that you wouldn’t be saying anything wrong but it is about how they can be misconstrued in the worst possible way.”10(Asad Dandia)

Dandia takes the concept of code-switching further to demonstrate the pressure to overcompensate to prove one’s innocence.

“You not only self surveil but you go out of your way to try to declare the opposite of what people would label against you. On the topic of Jihad for example, an Islamophobe or state entity might say that Muslims preach violent Jihad. A person who feels as if they’re being surveilled wouldn’t just not speak about it but they would only speak about it in that it refers exclusively to an internal spiritual struggle without talking about the classical jurisprudence on Jihad which had to do with military warfare. People don’t talk about these things even on a theoretical academic level.”11

The Importance of Community

One of the most important lessons, for Asad Dandia, was the resilience of strong communities and the necessity of having institutional support. The police was only successful in targeting and damaging individuals who were isolated or vulnerable to law enforcement on their own. Shamiur Rahman, for example, had been arrested on petty drug charges and seemed to be dealing with mental health issues. The NYPD offered him a way out if he spied on Dandia and other congregants. One individual, a convert to Islam who had previously been politically active, was entrapped by an undercover cop. Only eighteen years old, coming from an abusive family, and relatively isolated and vulnerable, a police officer began to cozy up to Justin Kaliebe, taking him out to dinner and coffee, and encouraging him towards a particular, incriminating political path. This infiltrator, masked as one of his only close friends, suggested that Kaliebe buy plane tickets to Yemen. Kaliebe was arrested at the airport for conspiring against the United States to fight with terrorists abroad.

For Dandia, these kinds of stories indicate the precarity of people outside the support of a familiar and intimate community. A strong community and access to institutional support, such as the ACLU, were the most effective mechanism of defence against surveillance.

“Institutional support and institutional power is really important. For those of us who have access to these institutions, we need to grapple with how we help uplift those communities that don’t have them, to inform them of their rights. For example, the Arab American Association of New York teaching undocumented people their rights in Arabic. At my mosque, there’s a know your rights campaign in Arabic, Urdu, Bangla, Turkish, and Farsi.”Elshinawy expressed similar sentiments. When asked about whether anything changed after the AP started reporting on surveillance and the ACLU got involved, he stated that there were “definitely less of those question mark personalities in my talks.” He attributes this to the fact that the police “would rather take advantage of people and scenarios that are not going to push back. It’s a trend that we’ve seen throughout our community.” A victim of surveillance showing awareness of their rights alone was enough to deter uniformed police officers. “When I said “listen, I’m not going to speak to you without a lawyer,” that was always the end of it, they never pursued the lawyers. Not once did they call up the lawyers and say let’s meet the three of us. They would rather just save themselves the headache and go to someone who will not demand their rights.”12(Asad Dandia (Plaintiff, Raza vs. New York), interviewed by Yasmeen Abdel Majeed and Anne-Laure White, New York, May 2017)

Conclusions

Code-switching is of course indicative of an external pressure forcing ecological changes, but it does not represent the death of a community so much as its adaptation to new circumstances. The court case offers a view of code-switching as a tool for survival, neither glorifying nor bemoaning it, but instead offering strategies for surveilled communities. Raza v. New York was an incredible victory not only for the plaintiffs but Muslims in New York in general. This project hopes to highlight the resilience of communities and individuals affected by the NYPD’s surveillance: an unjustified, unconstitutional, and discriminatory practice.

Case Documents

Below are a series of reports produced by the NYPD and published by the AP, as well as well as a document from the U.S. Eastern District Court. Click to view the documents.

Court Case Raza v. New YorkAlbanian Locations of Concern Report

Egypt Locations of Interest Report

Syrian Locations of Concern Report

Anne-Laure White:

B.A. American Studies, Columbia College, '17

Kurt Streich:

M. Architecture, GSAPP, '17

Rachel Fifi-Culp:

B.A. Urban Studies, Columbia College, '17

Yasmeen Abdel Majeed:

B.A. History, Columbia College, '18

Raza v. New York

Raza v. New York